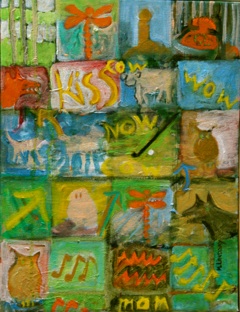

MOTHER/UNFRAMED

When I paint your body,

do I paint what's left behind?

No, I paint the soft light

spilling onto your last bed.

Did I irritate you when I tried to tell

you what business was like?

You bought me that suit anyway,

mahogany, thick wool weave,

snappy padded shoulders

and the long, slim skirt with a slit peeking out from a thick fold.

When I paint your body,

What am I fed?

Your estate's

numbers and forms

at my desk where I look

into the picture frames I took from your room:

photographs of babies, boys, young men --

my two sons growing.

I never put out pictures of my own.

When I paint the soft light

spilling on your bed...

You smelled of romance,

your teeth slightly crooked

when you smiled,

your glistening mink, fur deliciously cool--

when I buried my face, it tickled.

Your high heels clicking as you left, with Dad.

When I try to paint your body,

I paint something else instead.

We both married twice.

The first time you bought me a white leather book

to record crystal goblets and Tiffany spoons.

You ordered pale notepaper, monogrammed

with my new initials from a lead plate.

We both made long lists with our cross-looped letterings

in blue ink, now tossed together

in my attic in a box.

When I paint your body,

something unlocks.